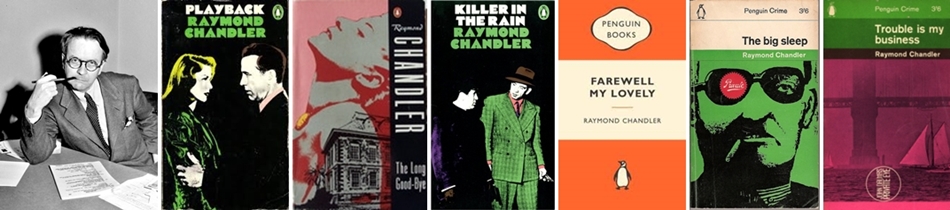

On this day, 26 March 1959, American crime novelist Raymond Chandler died. Here’s a look at his life and work.

(This article was originally published in 2005 and appeared in the British magazine ‘Chapter and Verse’.)

The Late Show

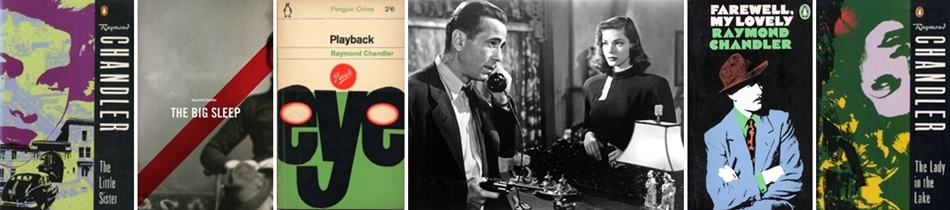

You can picture the scene, a world-weary private detective, gun in hand, walks warily down a corridor; opening the door he could chance upon a corpse or a beautiful lady or some hoodlum with a less than friendly disposition.

It’s all performed in a world of light and darkness, with no in-betweens, accompanied by sharp dialogue, wisecracks and the knowledge that this lone detective is just plunging further into trouble.

This clichéd scenario has been copied and used many times in countless books and films; both acting stalwarts Humphrey Bogart and Robert Mitchum have played such a cinematic role, but where did it all begin and why does it still hold an attraction today?

Back in 1933, in Los Angeles, Raymond Chandler began his writing career with the short story “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot” for Black Mask and went on to compose other short crime stories for pulp fiction magazines.

He was a late starter in life, beginning this vocation at the age of 45, but began to develop his skills and was keen to create something more realistic and had ambitions within the genre of crime fiction.

The short pulp fiction stories are good and total nineteen in all, but with titles such as “Trouble Is My Business” and “Killer In The Rain” they ultimately form the training ground of his career and some of the earlier ideas are expanded to form the foundation of his later, greater and more substantial novels.

It was then in 1939 his first novel “The Big Sleep” was published and introduced the iconic figure of Philip Marlowe, private investigator, a character “hard-boiled and soft-centered” as one critic astutely noted.

Set in Los Angeles, the opening pages emit so much style and a sense that the narrative has been beautifully crafted, that it’s immensely readable. Marlowe has been called to work for the General who “spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work show-girl uses her last good pair of stockings.”

His writing constantly possesses such deft touches of humour and the ability to say so much within the confines of one sentence. These quotes have been collected and admired by many, to the extent they are called ‘Chandlerisms’.

Age of Chivalry

The name of Marlowe was not his first choice, originally he had thought of ‘Mallory’, from Sir Thomas Malory the author of “Morte D’Arthur” a tale of Arthurian legends and the age of high chivalry. But his wife Cissy suggested ‘Marlowe’ – from Christopher Marlowe the Elizabethan poet, dramatist and forfeiter of life in a tavern brawl.

Either way it’s clear that Chandler always had literary pretensions and perceived Marlowe as an old-fashioned hero in a seedy and sordid L.A. Even the very first page of “The Big Sleep” has a stained-glass panel depicting a knight attempting to rescue a nude damsel in distress, who has conveniently long hair.

Chandler went on to write six more novels, and one could argue the recurrence and prevalence of similar themes throughout – Marlowe investigates the case, sometimes by accident, sometimes by design; becomes heavily embroiled (usually too emotionally) and it then all turns increasingly complicated.

The Crime Scene

However, talk of alleged repetition is to do a gross disservice to his ability to tell a great story with characters, while not arousing great feelings of sympathy, do have imperfections and struggle for existence on a grand scale.

The novels never really have a middle ground, which probably adds to their excitement and lack of mediocrity. It’s either way up high in a Hollywood director’s office or way down below in a sleazy downtown bar. Both worlds are criminal and Chandler doesn’t hide his contempt for either by blurring the edges between them.

Everything is good or evil and Marlowe is caught in-between with his conscience and sense of duty. And of course within each book there are some great lines that make you sit up and notice: “It was a blonde. A blonde to make a bishop kick a hole in a stained glass window.”

It’s questionable as to whether the books would appeal strongly to a female audience, especially if you look at the previous quote.

The main character is male and his environment is predominantly masculine – crime bosses ooze power and muscle, policemen harbour suspicion and cynicism, blood stains are fresh or dried out. While most women portrayed are never weak, they are very feminine, some highly intelligent and their charms are alluring and obvious: “She approached me with enough sex appeal to stampede a businessmen’s lunch.”

But it never should be misconstrued that Chandler disliked women or was unable to understand them. On the contrary he was devoted to his wife Cissy, who was a remarkable 18 years his senior, and her death in 1954 after thirty years of marriage left him devastated.

A sense of his personality from his books, letters, friends and colleagues reveal that he was outspoken, slightly irascible, sentimental and probably a hopeless romantic.

Music of Chance

Years ago when I was sitting my English Language or Literature exam (I can’t remember which), I chanced upon a question which utilised a line from Chandler’s second novel “Farewell, My Lovely” (1940): “Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.”

This brilliant sentence and image stuck in my mind to such a degree that it encouraged me to read his work. No author can really ask more than for a reader to be inspired solely by a random encounter with one of their quotations.

The novels “The High Window” (1942) and “The Lady In The Lake” (1943) are not his strongest by his high standards, with the former being Chandler’s least favourite and the latter requiring extensive rewriting and having been begun in 1939.

The subsequent “The Little Sister” (1949) was initially disliked by the critics, but personally it’s underrated and has an edge of humour and complication. It was published after a gap spent working on such classic screenplays as “The Blue Dahlia” and “Double Indemnity”.

But the perennially blunt Chandler never disguised his dislike for Hollywood and its workings, which is probably a case of biting the hand that feeds you.

An American Abroad

Chandler had openly criticised other authors for their lack of realism in the genre, and he had made it clear his desire to bring crime fiction away from the murder-mystery style of mansions and death by candlestick or poison, and back to the city streets and an examination of the underbelly of society.

This he does achieve, but with a heady cocktail of elegance and witticisms. And yet it was this style that might have encouraged his detractors to accuse him of lacking true grit and the real understanding of detectives and their business.

Fans of Dashiell Hammett, the creator of Sam Spade and author of “The Maltese Falcon” (1930) and a contemporary of Chandler, point out that Hammett had had real life experience at the Pinkerton Detective Agency and it showed with his authenticity and brutalism.

But while Chandler’s life was never so dramatic as Marlowe’s or involved working as a private detective, it nevertheless was interesting and naturally began with his birth in Chicago in 1888; time then spent living and studying in England, France and Germany; then a return to America in 1912 and a life in Los Angeles.

Like many writers he had a varied work experience, with jobs at the Admiralty and the Daily Express in England. There was even a stint in the Canadian Army during the First World War, while in America saw him work at a bank and in the oil business.

The Great Depression and his drinking and absenteeism led to his removal from the latter career, but as one door closes, another one opens, and he began writing for which he is known. Often imitated, but never bettered.

“The Long Goodbye” was published in 1953 and was lengthier and much admired by the critics.

Marlowe unintentionally hurtles headlong into the depths of darkness and there’s a lot of cynicism in the novel, with a frank description of Los Angeles: “It smelled stale and old like a living room that had been closed too long. But the coloured lights fooled you. The lights were wonderful. There ought to be a monument to the man who invented neon lights. Fifteen stories high, solid marble. There’s a boy who really made something out of nothing.”

When Darkness Calls

But Chandler was never going to die in a shoot out in a rundown motel or with an ice pick protruding from his neck. After the death of Cissy his life slowly petered out through heavy drinking, an attempted and clumsy suicide, tax disputes and illness.

There was a brief revival with the publication of the rather short novel “Playback” in 1958, and while lines like “On the dance floor half a dozen couples were throwing themselves around with the reckless abandon of a night watchman with arthritis” always bring a smile, this is the weakest of the seven novels and on 26 March 1959, Raymond Chandler died of pneumonia in Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, California.

He always admitted that he would rewrite and rewrite until he felt it was perfect and the result was that he was notoriously slow.

The result was only seven novels from 1939-1958, but in our present day and age where sometimes quantity overshadows quality, it’s reassuring to know that he stuck to his principles and strived to create literature that was truly memorable.