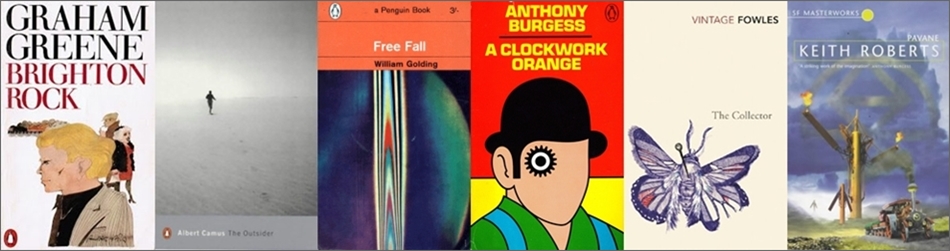

Here are six novels with such power and clarity that they remain a constant in the memory. Three of them have only been read once, but will be read again in the future. The others have been enjoyed several times (*) and their brilliance remains undimmed. It was tough to get the list down to six, but brevity is the goal here. By accident, rather than design, they only cover a 30-year period: 1938 to 1968.

Brighton Rock, Graham Greene, 1938*

“Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.”

The opening line gets your attention, and in fact the rest of the book never lets up. But this is much more than just a thriller and a world of seedy gangsters. Greene was a famous Roman Catholic and uses his compelling novel to examine sin and morality. The antihero Pinkie Brown represents the forces of evil – he’s a repressed and repulsive figure, but still convincing. His nemesis, Ida Arnold, seeks justice and wants to save a soul. The book’s title is a metaphor for the human character – no matter how deep you go, it’s always the same.

The Outsider, Albert Camus, 1942*

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don’t know.”

The cold, opening lines of this powerful French novel are bewitching and disturbing. The main character is Meursault, an indifferent French Algerian. It’s his detachment from society that drives the story and provides its existentialism theme. I could read it every year and still discover something new. Camus said: “In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” He added: “I only meant that the hero of my book is condemned because he does not play the game.”

Free Fall, William Golding, 1959

Golding is of course famous for the laudable Lord of the Flies (1954). But Free Fall surpasses that work in stunning style. An Englishman, Samuel Mountjoy, is held in a German POW camp during World War Two. A Gestapo officer questions him over an escape organisation. He denies involvement but is placed in isolation to await possible torture. In the darkness, and gripped by fear, Mountjoy reflects on his life and when freedom was lost. The long flashbacks he experiences are mesmerising for their grim details and emotional impact.

A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess, 1962*

“Oh it was gorgeousness and gorgeosity made flesh. The trombones crunched redgold under my bed, and behind my gulliver the trumpets three-wise silverflamed, and there by the door the timps rolling through my guts and out again crunched like candy thunder.”

Written in just three weeks, this dystopian novel is famous/infamous for its portrayal of extreme youth violence. It’s a subject that never really goes away – from the Mods and Rockers of the 60s to our 21st century knife-wielding gangs. The story is partially written in a Russian-influenced argot called ‘Nadsat’. Bright minds won’t struggle as context helps when learning a language. Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film catapulted the book into popular culture, but Burgess’ idea is about free will not overblown drama. The title A Clockwork Orange evokes the concept of ersatz goodness.

The Collector, John Fowles, 1963

A work of perfect symmetry. The first half is the kidnapper’s version of events. The second, the victim’s. This was Fowles’ debut novel and it’s astonishing how he captures the personalities of both characters – their lives, desires and fears. The kidnapper is a pitiful and despicable individual. The victim, Miranda Grey, is an art student and more understanding of the world. Fowles said the story explored “the danger of class and intellectual divisions in a society where prosperity for the majority was becoming more widespread”. I believe The Collector is better and more profound than that.

Pavane, Keith Roberts, 1968

“On a warm July evening of the year 1588, in the royal palace of Greenwich, London, a woman lay dying, an assassin’s bullets lodged in abdomen and chest. Her face was lined, her teeth blackened, and death lent her no dignity; but her last breath started echoes that ran out to shake a hemisphere. For the Faery Queen, Elizabeth the First, paramount ruler of England, was no more…”

This is the prologue to a beautifully written alternate history. With the death of Elizabeth I, England doesn’t defeat the Spanish Armada of 1588. In the aftermath Protestantism is destroyed and the Roman Catholic Church attains supremacy. Fast forward to 1968 (the same year as the novel was written) and England has a mid-19th century technology with steam traction engines and mechanical semaphore telegraphy. Roberts communicates some interesting ideas about this new world through a cycle of vignettes and linked stories. One critic noted that Pavane is reminiscent of the literary style of Thomas Hardy. I wouldn’t argue with that opinion.