When you hear the name Raymond Chandler it may sound faintly familiar or simply not register. That’s understandable as this great American author belongs to a bygone age. However, from the 1930s to the 1950s Chandler created a fine selection of short stories and novels within the crime fiction genre. These were hard-boiled tales of private detectives in cheap hotels and seedy bars. All set in a less than angelic Los Angeles.

He also brought a bit more to the table than mere clichés. Chandler had style and literary ambitions. He took crime fiction out of trashy pulp magazines and into the realms of great literature. The short stories are good but demonstrate a writer experimenting or honing his craft. It’s really when the first novel The Big Sleep is published in 1939 that Chandler enters his golden age of writing. The detective Philip Marlowe is a memorable creation – witty, principled, tenacious. Don’t take my word for all this. Chandler received praise from Ian Fleming, Somerset Maugham, W.H. Auden, Anthony Burgess and many others.

The influence of Chandler on popular culture is also far greater than most people imagine. Superb films like Roman Polanski’s Chinatown or the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski invoke the spirit of Marlowe. The hero descends into an abyss of confusion and danger, but at least he can make some jokes on the way. Chandler’s quips are so good they are known as Chandlerisms. His impact doesn’t end there. The video game L.A. Noire is Chandler’s world brought to the computer screen, while the SF TV show Star Trek: The Next Generation paid futuristic homage with The Big Goodbye. I could cite many more examples.

Chandler may have died in 1959, but his work lives on.

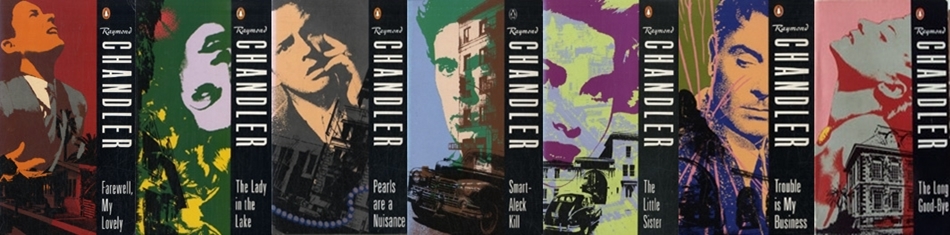

Over the coming months I’ll be reviewing his four short story collections: Pearls are a Nuisance, Trouble is My Business, Smart-Aleck Kill and Killer in the Rain.

These will be followed by all seven novels in chronological order: The Big Sleep (1939), Farewell, My Lovely (1940), The High Window (1942), The Lady in the Lake (1943), The Little Sister (1949), The Long Goodbye (1953) and Playback (1958).

I’ve read all of them several times since the late 1980s – but this is the first time I’ll be writing reviews. Hope you enjoy the ride.

Review Number: 6 (1 in Chandler series)

Review Date: 4 September 2015

Title: Pearls are a Nuisance

Author: Raymond Chandler

Country: United States

Publication Date: 1950 (collected stories and an essay / 1934 to 1944)

Genre: Crime Fiction

This collection published by Hamish Hamilton in 1950 consists of three short stories: Pearls are a Nuisance, Finger Man, The King in Yellow; and an essay The Simple Art of Murder.

Pearls are a Nuisance

(Originally published in Dime Detective, April 1939.)

“Mrs Penruddock’s pearl necklace has been stolen, Walter.”

“You told me that over the telephone. My temperature is still normal.”

“If you will excuse a professional guess,” she said, “it is probably subnormal – permanently.”

This is an entertaining tale of amateur detective Walter Gage. The case is simple – find the missing pearls.

Gage is an amusing but pedantic individual. At times the light-hearted story feels like P.G. Wodehouse has hijacked the typewriter. I think Chandler may have recognised after this effort that his stories were better when they were more serious – with any witticisms used sparingly. The humour should add to the scene, not dominate it.

There’s also his famous literary device that he used in other stories and novels to engagingly describe any action:

He snorted and hit me in the solar plexus.

I bent over and took hold of the room with both hands and spun it. When I had it nicely spinning I gave it a full swing and hit myself on the back of the head with the floor.

If you’re thinking a story about an amateur detective having to do all the footwork is preposterous, just look to our present day UK. The British police claim to have no resources and so many members of the public have to solve cases themselves. However, I doubt any of them have as much fun as Gage did in this short story.

Finger Man

(Originally published in Black Mask, October 1934.)

I used the automatic elevator and prowled along an upper corridor to the last door on the left. I knocked, waited, knocked again, went in with Miss Glenn’s key.

Nobody was dead on the floor.

Darker, deadlier and better than Pearls are a Nuisance. This story also introduces the detective Philip Marlow (note the spelling). He’s not fully-formed here – and lacks some style and wit. But as it’s a short piece that’s bound to happen and forgivable.

The premise is that Marlow (that spelling bugs me) is hired as a bodyguard for a guy intending to gamble big at a casino. Things don’t go as planned and murder rears its ugly head. I won’t say who gets the chop – but from there Marlow gets in way too deep. If he didn’t, we wouldn’t really have a story.

It’s actually very good and reads as well as his novels. There are plenty of great descriptions. Chandler could do a lot with so few words:

She was dressed in a blouse and plaid skirt with a loose coat over them, and a close-fitting hat that was far enough out of style to suggest a run of bad luck.

By the way, ‘finger man’ is an old American expression to describe a person who points out someone to be murdered or robbed. Not an admirable job – but probably ranks above journalist or politician. It’s a phrase lost in the mists of time.

The King in Yellow

(Originally published in Dime Detective, March 1938.)

She looked tall and her hair was the colour of a brush fire seen through a cloud dust.

A fine short story. The action begins inside the Carlton Hotel, with Steve Grayce, house detective. Chandler immediately captures this world of thankless tasks, jaded characters, and a hotel longing for better days.

Grayce has to deal with King Leopardi – a brilliant if somewhat surly trombonist – enjoying the bottle too much and making music late at night:

His face was flushed and his eyes had an alcoholic glitter. He wore yellow satin shorts with large initials embroidered in black on the left leg – nothing more.

From there we move out of the hotel and things get complicated. They also get melancholic. The whole piece has the air of sadness and injustice. This scene outside a funeral home captures part of that mood:

A swarthy iron-grey Italian in a cutaway coat stood in front of the curtained door of the red brick building, smoking a cigar and waiting for somebody to die.

The Simple Art of Murder

(Originally published in Atlantic Monthly, December 1944.)

Chandler liked to analyse people and situations. That’s clear from his stories and letters.

In this essay he examines detective/crime fiction and mystery novels. Sadly, some of the writers he discusses have not lasted the distance – they have been forgotten in our 21st century world of overpopulation, technological isolation and impatience.

It’s interesting to note that he felt the same way some people feel today. Our society is dominated by the interminable glut of vapid news and Twitter – way too much information… and most of it superfluous:

In my less stilted moments I too write detective stories, and all this immortality makes just a little too much competition. Even Einstein couldn’t get very far if three hundred treatises of the high physics were published every year, and several thousand others in some form or other were hanging around in excellent condition, and being read too.

He was an anglophile. Born in Chicago in 1888 but his family emigrated to England when he was 12. He studied in France and Germany, and returned to London in 1907. In 1912 he went back to America. Parts of this essay reflect his love of English manners and class (when the country had them).

Chandler is also gracious to his contemporary and rival Dashiell Hammett (author of The Maltese Falcon):

He had style, but his audience didn’t know it, because it was in a language not supposed to be capable of such refinements.

A dated essay, but enjoyable thanks to Chandler’s intelligence, perception and opinionated views.