The fifth part in a series of 11 book reviews.

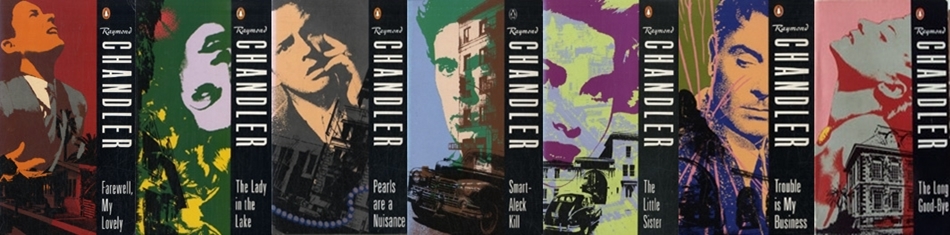

From the 1930s to the 1950s Raymond Chandler penned a stylish collection of short stories and novels within the crime fiction genre.

Over the coming months I’m rereading his work and writing reviews. More details about the who, what and why are explained here in part one.

Review Number: 10 (5 in Chandler series)

Review Date: 21 November 2015

Title: The Big Sleep

Author: Raymond Chandler

Country: United States

Publication Date: 1939

Genre: Crime Fiction

The General spoke again, slowly, using his strength as carefully as an out-of-work show-girl uses her last good pair of stockings.

A critic once said this novel was best read in one sitting. Good idea. On a cold, wet Sunday afternoon you could lose yourself in a laconic Los Angeles of deceit and death.

The Big Sleep is Chandler’s debut novel and he pretty much nailed it on the first go. Some people think of this as the perfect crime novel. It’s probably his most famous.

Where his short stories had been good or very good, this book, published in 1939, is assured and masterly. The space suits him better. He has time to let the plot develop and mature – and to twist and turn.

The opening page sets the mood and the thinking behind the main character, Philip Marlowe, private detective:

The main hallway of the Sternwood place was two stories high. Over the entrance doors, which would have let in a troop of Indian elephants, there was a broad stained-glass panel showing a knight in dark armor rescuing a lady who was tied to a tree and didn’t have any clothes on but some very long and convenient hair. The knight had pushed the vizor of his helmet back to be sociable, and he was fiddling with the knots on the ropes that tied the lady to the tree and not getting anywhere. I stood there and thought that if I lived in the house, I would sooner or later have to climb up there and help him. He didn’t seem to be really trying.

This is key to all seven novels. Chandler sees Marlowe as a knight in (shining) armour. The great detective is always on a quest for justice. But he’s cynical and shrewd enough to look around at the shady world he inhabits. There isn’t a page that doesn’t shine with wit and intrigue.

The case seems simple enough. General Sternwood, a rich and dying man, wants a blackmailer off his back. However, his two young daughters – double the trouble – cause quite a few problems to Marlowe as he tries to right a multitude of wrongs.

Let’s not forget, Chandler wrote this when he was 50 years old. A late show, but worth the wait. The book was an instant success and spawned films of varying quality, a host of imitators and a lasting influence.

It’s worth mentioning the two films.

The 1946 version, directed by Howard Hawks, with screenplay help from William Faulkner, is the classic that firmly put the name The Big Sleep into the limelight. It’s a great film and Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall are superb. Well worth a watch, but it does differ from the book in a few places.

Last and least. Avoid the 1978 film version. Directed by Michael Winner (a name that guarantees it will be trash) and starring Robert Mitchum. He was a great actor in his prime, but by 1978 was way too old for the part.

Winner, being a loser, decided to set the film, not in 1930s Los Angeles, but in 1970s London.

This misses the whole point of Chandler’s world. Los Angeles was and always will be integral to the mood and plot. Criminals, cops and other cast members are bound by the Californian climate, culture, corruption, and the special ‘rules’ for the rapacious rich of Beverly Hills and Hollywood. Take that away from Marlowe and you’ve not got much left.

The Big Sleep will always be a great work of crime fiction. No film can ever ruin its presence, power and panache.

What did it matter where you lay once you were dead? In a dirty sump or in a marble tower on top of a high hill. You were dead, you were sleeping the big sleep, you were not bothered by things like that. Oil and water were the same as wind and air to you. You just slept the big sleep, not caring about the nastiness of how you died or where you fell. Me, I was part of the nastiness now.