The Chronicles of Narnia by C. S. Lewis will be well known to many. A magical world of classic fantasy written for children, but enjoyable to any age group. Images that spring to mind from the land of Narnia will probably be a talking lion, a cruel witch and of course the famous portal – a wardrobe.

These seven books may have been written in the 1950s but their appeal is still strong. Sales have reached 100 million copies in 47 languages, a testament to their allure.

The books arguably have a Christian meaning – genesis, resurrection, temptation, etc. Lewis – who was a believer – saw them as “supposals” rather than allegories. If you’re an atheist like me, it won’t matter. Just appreciate the exciting and wholesome adventure for some simple escapism.

I first read the enchanting books at primary school and have enjoyed them many times. However, it has probably been about 30 years since the last rereading, so it’s time to explore them again and share some spoiler-free reviews.

Each tale is beautifully illustrated by Pauline Baynes. They are also slim affairs – one story can be read in about three to four hours. With that in mind, the reviews will be reasonably concise as over-analysis is not desired.

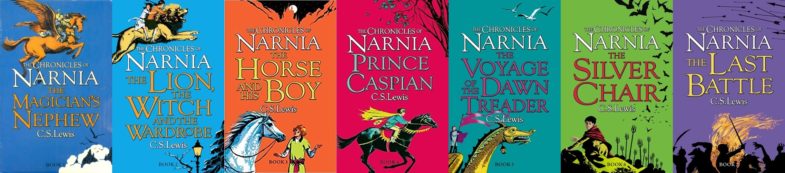

The reading order is open to debate. However, they will be reread in (Narnian) chronological order – and not the date they were published: The Magician’s Nephew (1955), The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), The Horse and His Boy (1954), Prince Caspian (1951), The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952), The Silver Chair (1953) and The Last Battle (1956).

Review Number: 17 (1 in Narnia series)

Review Date: 14 July 2020

Title: The Magician’s Nephew

Author: C. S. Lewis

Country: United Kingdom

Publication Date: 1955

Genre: Fantasy

For what you see and hear depends a good deal on where you are standing: it also depends on what sort of person you are.

What better way to start an adventure than immediately introducing two children precisely looking for that?

In the summer of 1900, a pair of youngsters – Polly and Digory – go through ‘the wrong door’ and stumble on the boy’s uncle and his highly unusual travel experiment.

With skill and ease, things move at pace as they visit the wood between the worlds (a memorable multiverse moment), and onto new realms and dangers. Let’s not give too much away but the children are prepared to talk back, argue or express opinions strongly. Lewis depicts an England not as a place of blind obedience, but one encouraging independent thought. That refreshing part had escaped the memory.

What is great about this work of mid-20th century literature is that events develop with energy. The children are pragmatic, brave and possess the dying art of common sense.

There’s no unnecessary apologising or lengthy explanations by the author. At times Lewis makes a moralistic point. But it’s done with succinct wisdom.

The official Narnia website notes: “On a daring quest to save a life, two friends are hurled into another world, where an evil sorceress seeks to enslave them. But then the lion Aslan’s song weaves itself into the fabric of a new land, a land that will be known as Narnia. And in Narnia, all things are possible.”

In a clever reference, the book’s title comes from Digory – for he is the magician’s nephew to this rather intense uncle. Lewis originally titled the novel Polly and Digory, but while they are the centre of attention that option doesn’t have a mystic edge to it..

Lewis published The Magician’s Nephew near the end of his Narnia saga. It was written to cater to queries of where the world all began.

This book is the ‘genesis’ and where we first meet the lion Aslan, the Christlike figure. (If you didn’t know, Aslan is Turkish for ‘lion’.)

We only get a taste of Narnia but as it’s the birth of a nation, that’s why I prefer to read it first. It neatly sets the scene for the rest of the series and why some foreign elements exist.

The Magician’s Nephew is not the best of the Narnia novels if my recall is correct, but as an introduction – and for its exploits – it is certainly not disappointing.

“All get what they want; they do not always like it.“